If these were really the reforms contemplated, I could not see what objections the Dalai Lama could have to them. The US ambassador, however, although he was a connoisseur of historical and cultural issues of Asia, could not avoid comparing the Ch’ing Empire with a federal state and about this he wrote to President Theodore Roosevelt:

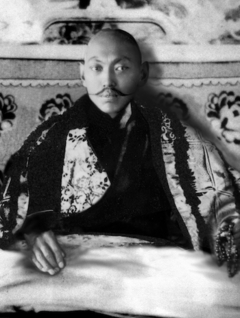

13th dalai lama series#

The country, to be divided into administrative districts «as in China proper», would have been then hit by a series of reforms, to regulate the military, the infrastructures, monetary system, education and agriculture.

A couple of weeks later, Dorjiev, who was in Peking with the Dalai Lama, shared the latter’s worries with Rockhill: Thubten Gyatsho saw his temporal power over Tibet threatened: after less than two centuries of substantial autonomy within the Manchu imperial system, Ch’ing Dynasty was rethinking the political and administrative status of Tibet. At the meeting there were no Chinese, and the American diplomat found Thubten Gyatsho “in a much less happy frame of mind than when I had seen him last he was evidently irritable, preoccupied, and uncommunicative”. Just two days before, on October 6, the Dalai Lama met with William Woodville Rockhill, the US ambassador. For this reason, on October 8, 1908, the Wai-wu pu informed the Doyen of Diplomatic Body the days and times at which the foreign delegates could meet with the Dalai Lama, and only after they have been received and presented by a Chinese officer. This created a certain discomfort with the Government of China. While in Peking, Thubten Gyatsho had the opportunity to have direct or indirect contacts with several Western representatives: an envoy had gone to the British, Russian, German, American and French legations and Ministers of Washington and Paris had a private audience with the Dalai Lama.

The audience, originally scheduled for October 6, also because of ceremonial matters, was then fixed for Octo. ’Jam-dpal-dbyangs) and therefore Thubten Gyatsho knelt to the sprul-sku and not to the political leader of the Empire. The successor of Thubten Gyatsho, the fourteenth and current Dalai Lama Tenzin Gyatsho ( Bstan-’dzin-rgya-mtsho), gave a purely religious interpretation to that genuflection: Tibetans considered the emperor as the body of manifestation of the bodhisattva Mañjuśrī (tib. Thubten Gyatsho had made no secret of his opposition to such a gesture, which would have been therefore replaced by a simple kneel. The reason for the different treatment given to the thirteenth Dalai Lama, in comparison to the one of the visit in the seventeenth century by the Great Fifth, was the intervention of Chang Yin-t’ang who had advised the government on the procedure to follow with the spiritual leader of the Gelug-pa.

He reached the city by train, at two in the afternoon, greeted by representatives of the Wai-wu pu, Li-fan yüan and of the imperial family.Īmong the conditions for the audience that the Emperor Kuang-hsü and the Empress Dowager Tz’u-hsi would have granted the Dalai Lama there was the k’ou-tou, or the act of prostration before the emperor. The thirteenth Dalai Lama Thubten Gyatsho ( Thub-bstan-rgya-mtsho) arrived in Peking on September 28, 1908. Matteo Miele* examines the diplomatic activities of the 13 th Dalai Lama in Beijing during his escape there in the aftermath of the British invasion of Tibet in 1903-04, which explains why he made the 1912 declaration of Tibet’s independence: that whereas Tibet viewed itself as an independent country forced to remain subservient to the wishes of its powerful neighbour, China not only considered Tibet a part of its empire but also looked to fully integrate it in ways unprecedented in history and which the communist Chinese eventually carried out in 1959. This article appeared in the March-April 2015 edition of Tibetan Review. The Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Thupten Gyatso

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)